Loss, a retired correctional social worker and piano/guitar player, and Charles, a personal fitness trainer and musician/songwriter, met as trainer and client. After Maria died in 2019, Loss made several attempts at songwriting that proved fruitless. He also began working with a new personal fitness trainer at his local gym, Charles. The two shared stories of grief, because Charles, too, experienced loss in his life. Soon the conversation turned to music, and the two began sharing a love of music from the 1960s and 70s.

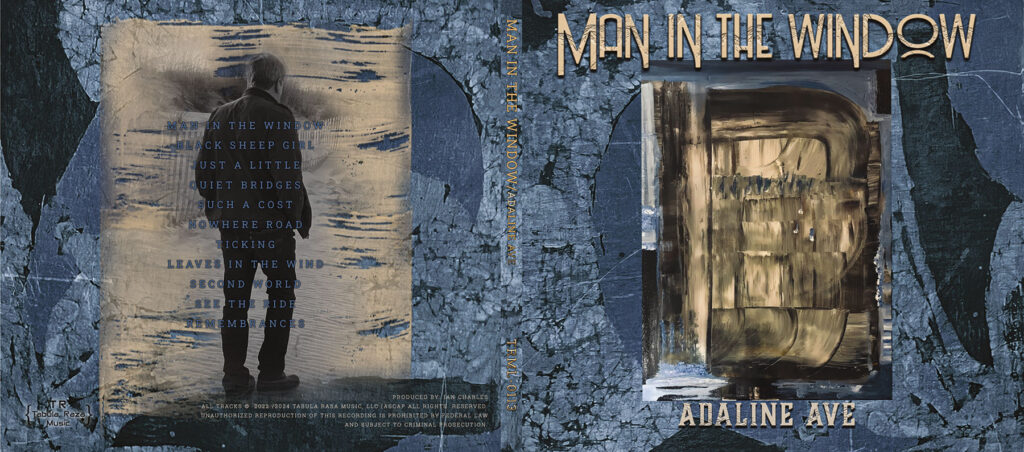

An instant bond developed. At age 67, Loss began writing songs and showing lyrics and music to Charles, and the two friends began to collaborate on this first album together. Adaline Ave marks Loss’ first musical venture and Charles’s return to music. Along with talented musicians and engineers, and family members singing too, Adaline Ave became a tribute to Maria and an unexpected conduit for grief and sadness.